‘Freedom’ is a short film produced in 2018, during the notorious border crisis which continues today.

The short stars Giselle Itié (‘The Expandables’), and it uses a parody car commercial and its typical narrative of rugged individualism and, well, freedom, as a basis for exploring the incredibly harsh realities of the border crisis and undocumented immigration from Central America to the United States.

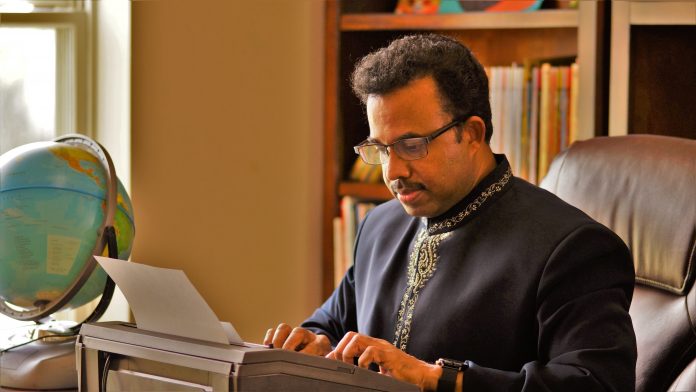

‘Freedom’ was written by Eduardo Albuquerque, an experienced screenwriter who knew that he wanted to address these conflicting narratives in his work while also making use of his signature manipulation of reality, whether it’s the reality we all experience or the reality that has been established in a film.

Following selection for a number of different film festivals, such as the Berlin Flash Film Festival, the Houston Latino Film Festival, Immigration Film Festival, and Oaxaca Film Festival, ‘Freedom’ also won multiple awards.

Albuquerque agreed to join us for an interview to discuss ‘Freedom,’ including the ideas that first inspired the overall concept and the rapid production timeline, which was partially motivated by the urgency of the film’s messaging.

You’ll find the full interview with Albuquerque below. If you’re interested in learning more about the film, you can check out the IMDb page here, and you can watch the full short here.

We’d like to ask you about your short film, ‘Freedom.’ Where did the initial idea come from?

Albuquerque: It was the early years of Donald Trump ‘s administration, and I was seeing all the horrible news about what was going on at the border, with kids being separated from their parents. I felt like, being a legal non-immigrant with a voice, I needed to say something regarding that nonsense.

I remembered a conversation I had had with Yuri and Ana, the duo who directed ‘Freedom,’ where they mentioned they needed to shoot something with cars so their agent could get car commercials for them, and I just put one and two together.

I called them and said, “Isn’t it crazy how most of the big money-making car commercials promote these ideas of ‘freedom’ and people applaud it, but when it comes to immigrants running for their lives it becomes controversial, to say the least?”

So I wrote the script. We all loved it and decided to do it.

Did this film have a lengthy pre-production process?

Albuquerque: I’ve written feature films that took five years from writing the final “Fade to black” on the page to hearing “Action!” screamed on the set, so actually this was pretty fast.

It took about two months. Which isn’t to say it was easy! That’s another story. We had a crew made almost completely of immigrants. We shot in the Mojave Desert, Giselle Itié flew from Brazil and had a pretty tight schedule. So it was a pretty complex one to pull off.

But I guess that’s the thing when you’re making something with purpose. We knew we were doing something important. It’s something a lot of those people who die or lose everything trying to get a new chance at life in “the land of opportunity” would dream of doing. So we managed to focus, beat the heat and the fatigue, and do it all in one day.

Were you involved in the casting process at all?

Albuquerque: I was. Being a former actor, I always like to write specifically for my actors, considering the way they speak, act, and move. I’ve been extremely lucky to have written for amazing actors throughout my career.

Marcelo Adnet, Dani Calabresa, Gregório Duvivier, Augusto Madeira, and now the amazing Giselle Itié. She was born in Mexico, which made it personal for her, too.

The day she read the script, she had just seen footage of a two-year-old being reunited with his mom after three months apart and not recognizing her; just a horrible horrible scene. She called back and said, “Ok, I’m doing this. I’m finding space in my schedule.”

She was about to start filming Netflix’s ‘The Chosen One,’ and I was so happy to fly her over and contribute with her amazing acting.

What would you say is the film’s most crucial scene?

Albuquerque: I have to go with the big twist or reveal at the end. It’s a wonderful moment when you’re in the theater and you can hear the air getting denser because everyone is out of breath. It’s the moment the short’s been made for. To provoke that “Damn, you’ve unarmed me and now I’m vulnerably willing to empathetically think about what you’re saying,” in the audience.

How did you expect audiences would respond to the film?

Albuquerque: My stories usually deal with a sort of manipulation of reality, specifically manipulation of the audience’s expectations or the narrative world built within the story itself.

With ‘Freedom’ I expected the audience to get pulled into the car commercial narrative only to have the ground beneath their feet open to a world of pain, which would make them realize something was wrong with how this issue was being handled.

But what was interesting and something I wasn’t expecting was how the film resonated differently when it came to gender. Men tend to laugh out of nervousness and get angry. Now, to women, this is no joke: the threat of having other people, mostly men, deciding what to do with what should be hers is all too real and present. They tend to stay silent and attentive and usually get teary-eyed.

When you saw the film was earning awards at multiple festivals, did it feel like a moment of validation?

Albuquerque: Festivals are nice, especially when you get to attend and check out your peers’ work and hang out with other screenwriters. It’s one of the rare moments when screenwriting becomes less of a lonely job.

But regarding the many awards, I think they validate the movie, not necessarily me. I was elated because awards make people pay more attention to the movie, and I just wanted ‘Freedom’ and its message to reach as many people as possible. Indifference is the artist’s death.

Do you ever go back and rewatch this film? If so, does it feel different to you now?

Albuquerque: I do! That’s the beauty of short films and short stories: you don’t need the time commitment a TV series or a feature requires. It’s an easy way to show your work whenever you meet someone new that asks, “Where can I see something you’ve done?”.

It does feel different. It feels less urgent and heavy now, which is great. And I don’t want to be that Debbie-downer kind of a guy, but I think it will always be relevant and worth revisiting as a way to remind us that it’s great to celebrate accomplishments, but this is a constant battle.

It’s important to revisit this subject and not normalize it. We have to make sure we continue fighting for it not to happen anymore.