As a management consultant and executive coach, I often attend important presentations to boards of directors, senior management, and top customers. Despite the fact that many presenters have excellent technical skills, are well-versed in their fields, and really care about their audiences, their presentations often confuse rather than convince them.

It’s amazing how many people leave a meeting room or a Zoom session with a worse opinion of the speakers’ competency or skills than they had before hearing the presentation.

A pitch or report may be ruined by a variety of presenting abilities. Here’s one area that’s frequently ignored, but which I’ve seen cause issues time and time again — as well as some things you can do to help.

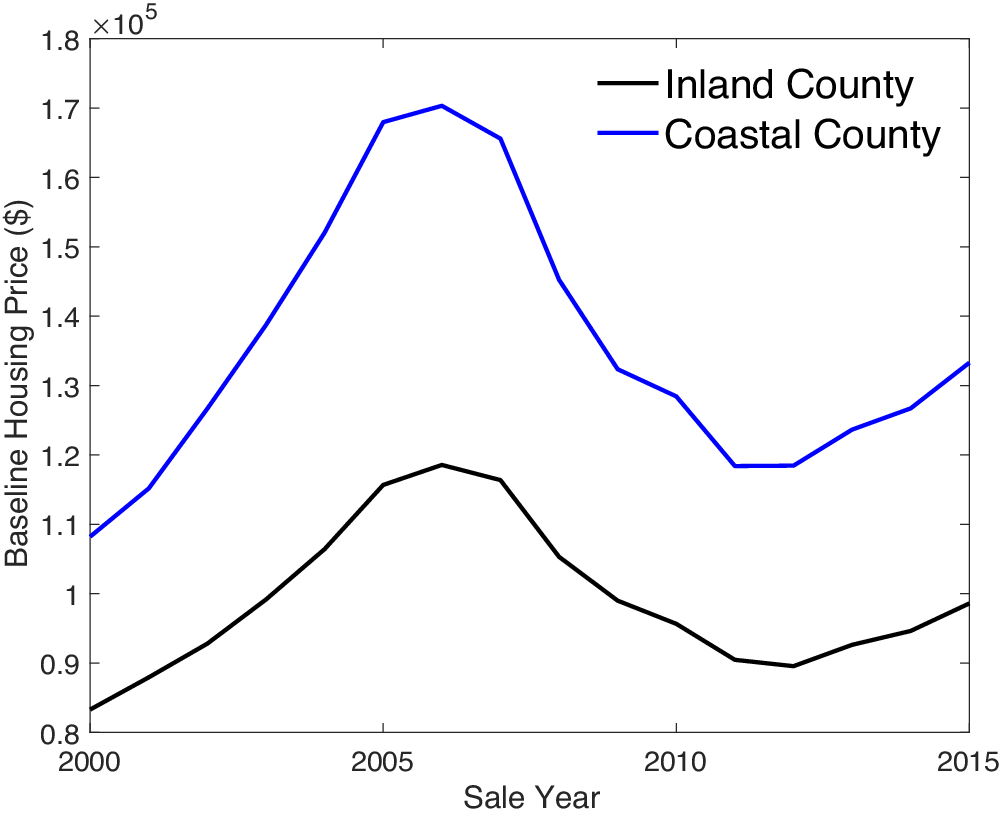

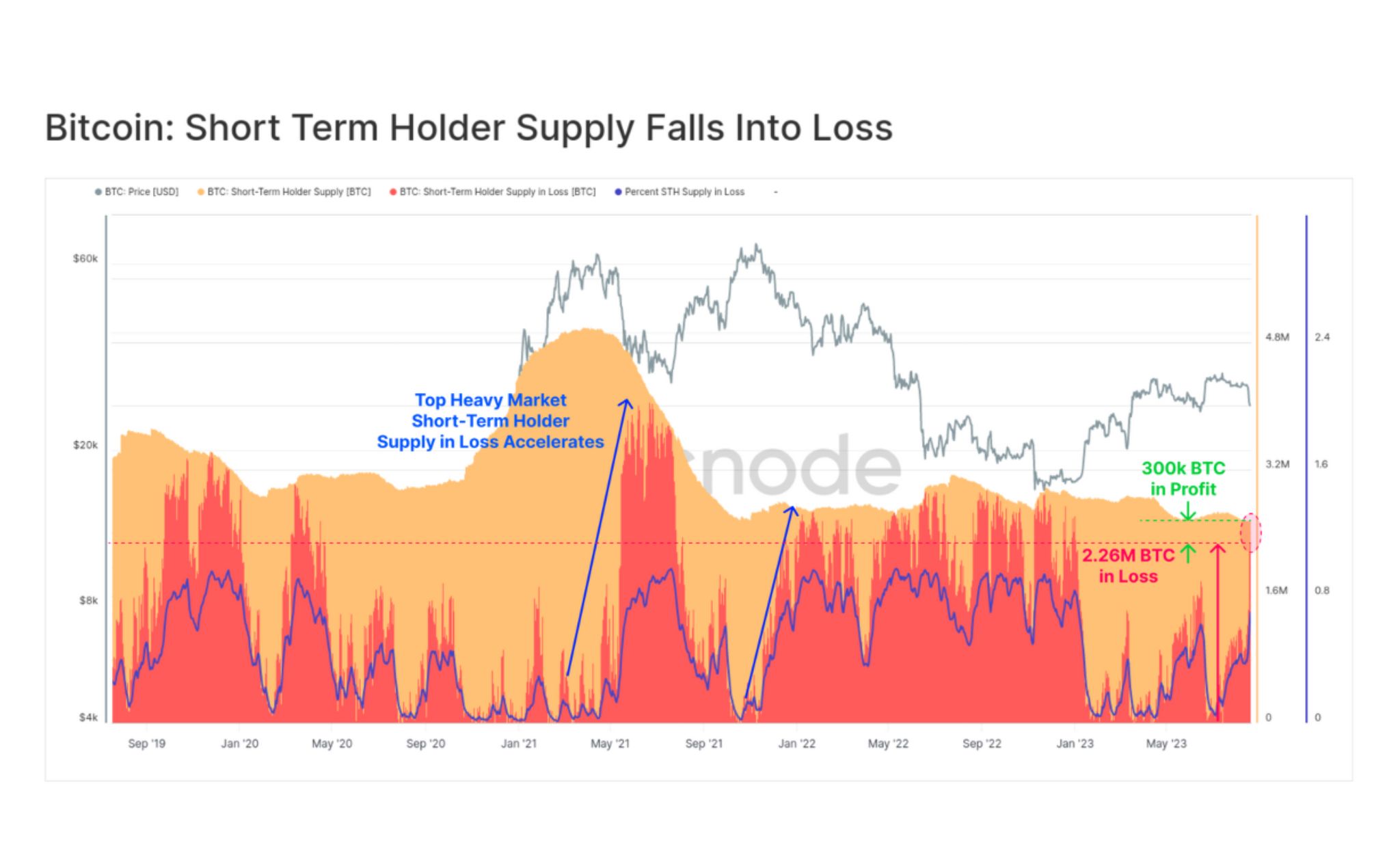

Don’t Assume People Understand You Focusing on technical material rather than the problem or topic that the audience cares about is one of the fastest ways to turn off an audience and ruin your connection with them. It doesn’t have to be as complicated as physics or biology; it may just be quantitative data on memberships or new hires.

However, it may be difficult for individuals who work with data every day to convey the details in a manner that the audience understands in context without requiring extensive research.

Even if you’re presenting to a leadership team that hears your report every month, keep in mind that they won’t be as acquainted with the terminology and jargon as you are, and therefore may forget what those words mean. That implies they’ll be two minutes behind you in your presentation, not truly comprehending what you’re confidently reviewing.

This creates an odd dynamic in which the audience’s lack of comprehension may lead to a lack of trust and confidence in you and your facts, regardless of how knowledgeable you are. They’ll say to themselves, “I’m smart enough to understand this stuff, so something’s wrong because this doesn’t make sense to me.”

And they’re speaking so quickly! “What are they attempting to conceal?”

Drill to the core to establish context and understanding

Drilling speakers (or yourself) over and over again with the question: “What is the point/takeaway/thing you want the audience to understand?” is one thing that helps — though it is admittedly a terrible practice.

So, what proof do you have to support that claim?” Otherwise, technically skilled presenters tend to go from detail to detail, drowning the audience with facts and data they don’t fully understand and omitting key topics.

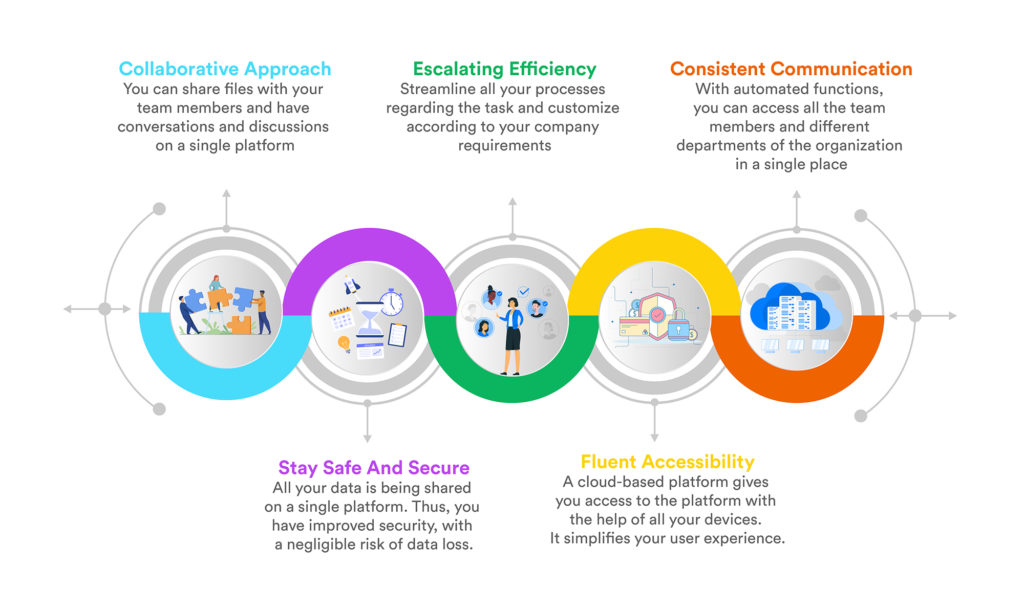

In theory, you want to gain the audience’s comprehension straight immediately so that they will take action that moves them closer to your goal. So, before you start putting together your presentation, consider where you and your audience have a common interest: “What is our shared mission or goal?”

What is the state of affairs right now? What exactly is their/my/our issue? How will my solution contribute to solving the issue as a whole, rather than simply my own?”

Before you start drafting a PowerPoint presentation, consider your responses to these questions. This ensures that your narrative has an arc rather than simply a collection of important information that seem disjointed to others who don’t know what you know or who may forget what you’ve previously told them.

All questions should be taken seriously and answered slowly. Similarly, if you bounce from technical word to technical term or number to number to attempt to give a fast solution to a leader’s particular issue or concern, you risk undermining your credibility – either during your presentation or in response to inquiries.

To make your technical responses more appealing, connect them to a human or organizational purpose or narrative, even if it means pausing for a few minutes before responding. “That’s a fair question,” you might say.

Allow me to consider how I could utilize the facts to depict the position we’re in and our options…” Then, rather than just throwing numbers about, really talk carefully enough to create a through-line.

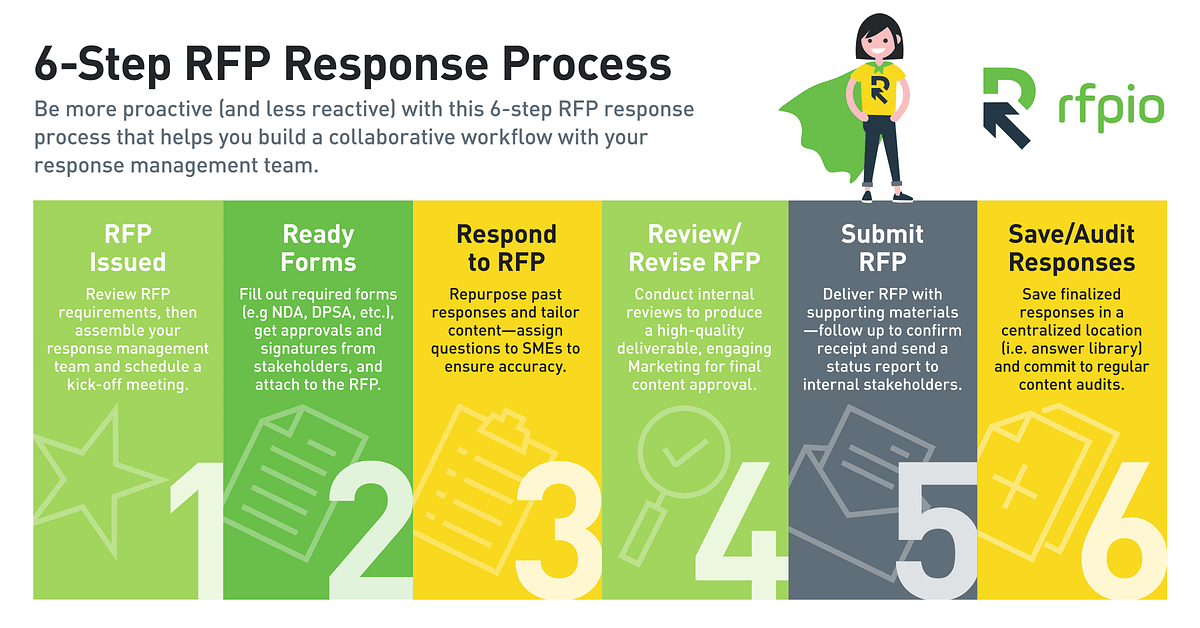

Assume you’ve been requested to demonstrate a link between your plan for better working conditions and staff retention by a skeptical leadership. You might say something like this in your response:

- “As you all noted in our most recent quarterly business report, we’ve been losing too many good people as a result of…” [description of the problem/thanking the leaders]

- “We looked into it and discovered…” [responsiveness demonstration]

- “As a result, we advise that the following practices be changed…” [proposal]

- “This should lead to…”, says the narrator. [benefit]

- “…however, we acknowledge that the following drawbacks could also occur…” [display of danger]

- “…with which we are attempting to deal…” [risk reduction]

- “We’d like to be able to explain this to the team in the following order…” [Plan of Execution]

- “All right, let me take you through the data that demonstrates why this is so critical.” [evidence for support]

Your Pitch’s Backers

It doesn’t matter how persuasive your arguments are if they aren’t relevant to your audience’s day-to-day concerns. Whether or not they understood you and believed you were trustworthy, they’re more likely to notice their own emotions of comfort or discomfort.

So, before you start your slide presentation or start the conversation, double-check that you’re utilizing data and proof to back up your claim, rather than dragging the audience through a maze of facts and numbers they don’t understand.

Thanks to Liz Kislik at Business 2 Community whose reporting provided the original basis for this story.